December 8, 2017 @ 3:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Event Navigation

Small solar system bodies are generally covered in layers of particulate “regolith” with largely unknown properties. The effective gravities on these bodies can sometimes tend to zero at the equator, and have been measured to be negative in a few cases. Space agencies and commercial enterprises show increasing interest in visiting, landing on, and sampling from such bodies, so it is important to understand how the regolith will respond to intrusion. Due to the difficulty and expense of carrying out experiments in low gravity, we turn to computer simulations of granular dynamics to provide insight into the conditions that missions to other worlds may encounter and to help interpret observations of these bodies.

As high-end computing resources become more readily available, granular dynamics simulations have become more sophisticated, treating particle collisions as finite-duration, multi-contact events with explicit friction forces between irregularly shaped grains subject to external forces, boundary conditions, and cohesion. It is imperative that such simulation methods be calibrated and validated at laboratory scales to give confidence in their application to other environments. Here I review our group’s approach to simulating granular dynamics in low gravity, with examples that include impacts into granular materials, vibration-induced segregation, landslides, models of samplers and landers, and, on larger scales, simulations of entire granular bodies (rubble piles) and planetary rings.

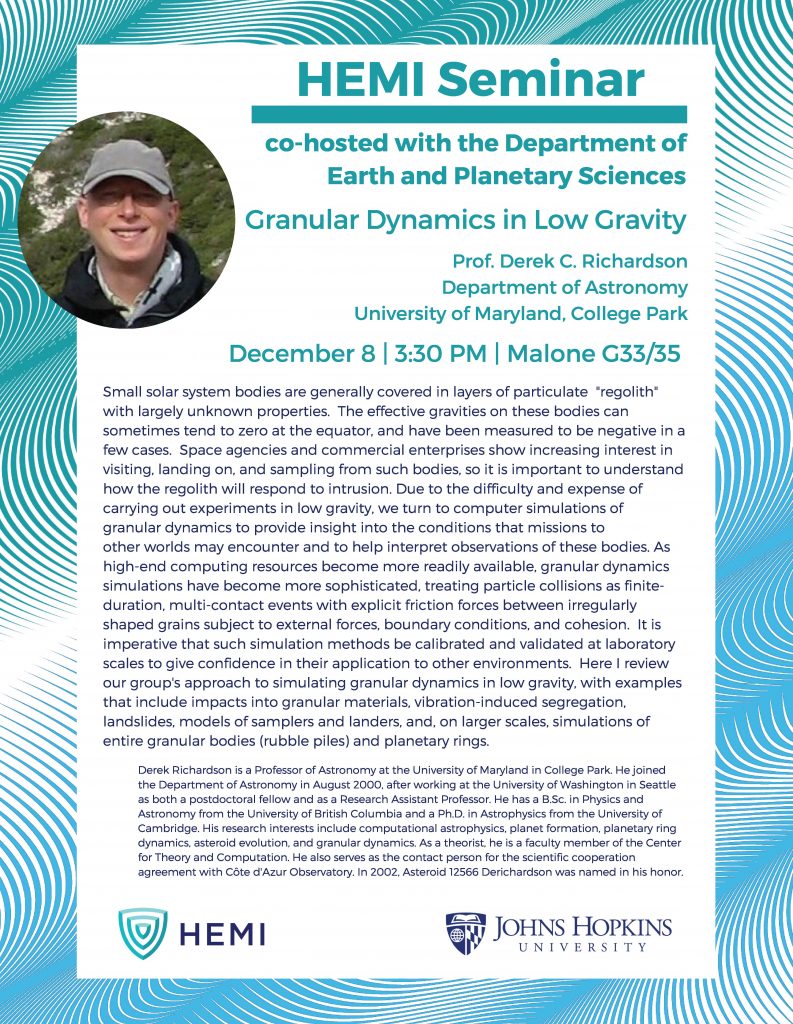

Derek Richardson is a Professor of Astronomy at the University of Maryland in College Park. He joined the Department of Astronomy in August 2000, after working at the University of Washington in Seattle as both a postdoctoral fellow and as a Research Assistant Professor. He has a B.Sc. in Physics and Astronomy from the University of British Columbia and a Ph.D. in Astrophysics from the University of Cambridge. His research interests include computational astrophysics, planet formation, planetary ring dynamics, asteroid evolution, and granular dynamics. As a theorist, he is a faculty member of our department’s Center for Theory and Computation. He also serves as the contact person for the scientific cooperation agreement with Côte d’Azur Observatory. In 2002, Asteroid 12566 Derichardson was named in his honor.